Our logo

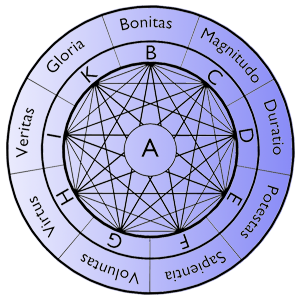

Inspired by Ramon Llull

Ramon Llull (1232-1316)

- Johnston, Mark D.

- The spiritual logic of Ramon Llull. - Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1987.

Sometime in 1263 or 1264, however, Llull underwent a profound religious conversion, induced by repeated visions of Christ crucified. At this time Llull is said to have conceived the three great goals of his life's work as a missionary and procelyte; these form the indispensable context for any understanding of his doctrines and activities. They were: (1) the founding of schools to teach missionaries the oriental languages, (2) the writing of a book to prove Christian doctrine, and (3) the propagation of the Faith among the infidels. Inspired by a Franciscan sermon, Llull renounced his life at court, sold all his goods, and went on pilgrimages to Rocamadour, Compostela, and other shrines.

Returning to Barcelona in 1265, he met Ramon de Penyafort, the redoubtable former Dominican Master-General, who approved Llull's goals, but urged that he prepare himself adequately in advance. Consequently Llull returned to Majorca for nine years of study, which included learning Arabic from a Muslim slave. He seems to have acquired the rudiments of a traditional medieval arts curriculum education, and acquainted himself with the literature of Augustine, Anselm, the Victorines, and Franciscan authorities, perhaps by reading materials available at the Dominican and Franciscan churches then existent in Palma de Majorca. Similarly he acquired some knowledge of traditional Islamic theology and philosophy, apparently from their more popular manifestations among the various schools or sects of Majorcan Islam, and from versions (perhaps excerpted) of the works of great Arab authorities such as Algazel. Dominique Urvoy has noted, however, that it is unlikely that Llull would have found any Islamic teachers capable of expounding Arab philosophy to him in a very sophisticated way. During these years Llull produced the Arabic versions (now lost) of his first works: a compendium of the Logic of Algazel, the Libre del gentil e los tres savis, and the Libre de contemplació en Déu, a seminal work and the first of Llull's encyclopaedic compilations.

In 1274, Llull received an intellectual 'revelation' on Mount Randa near Palma, which effected the transformation of his nascent doctrine of Divine Dignities or attributes of the Godhead into a global meta-physical system. The first Ars magna, or Ars compediosa inveniendi veritatem, completed shortly afterwards, was the first redaction of this system, the famed Lullian Art. In 1275 Llull left Majorca to seek the patronage of his former associate James Il, now ruler of Majorca, Roussillon, Cerdanya, and Montpellier. He thus began a life of nearly continual peregrination. Llull's works were approved by a friar minor appointed to inspect them by James Il. Llull then received approval for establishing a monastery at Miramar on Majorca; this was founded in 1276 with thirteen Franciscans who were to study the Liberal Arts, Theology, oriental languages, Islamic doctrines and Llull's own Art. Its foundation was confirmed later that year by Pope John XXI, Peter of Spain. Very little is known about the subsequent ten years of Llull's life, except that he continued to produce works in Latin, Arabic, and Catalan. These included tracts advocating his missionary plans and perhaps his literary masterpiece, the Libre de Blanquerna.

The death of Pope Honorius IV (3 April 1287) and Llull's lack of academic credentials frustrated his attempt to obtain a papal hearing at Rome that year for his proposals. He went then to Paris, where he was licensed by one of the Chancellors, Bertaud de Saint-Denis, and authorized to teach his Art. This licence indicates that Llull must have possessed some academic qualifications, but their source or nature is uncertain, and licensing requirements were still flexible at this time. In Paris he began his long conflict with the Latin Averroists and found a new and powerful patron in Philip the Fair of France, nephew of James II; James was now weakened by the loss of Majorca in I285 to nephew Alfonso III of Aragon. Returning to Montpellier in In 1289, Llull wrote several works and composed a second, more simplified, redaction of his Art, the Ars inventiva veritatis. About 1290 Llull began an association with the Spiritual Franciscans, whose unorthodox millenarian doctrines were commonly associated with him even during his own lifetime, although he rejected their views and wrote several anti-Spiritual works. Llull knew well the notorious Arnold of Vilanova who, since the death of Peter John Olivi, was the leading Spiritual of the time. The Franciscan Minister-General Ramon Gaufredi, deposed by Boniface VIII in 1295 for his tolerance of the Spirituals, met Llull in 1289 during the Chapter-General of the Order at Rieti, and authorized Llull to teach his Art to Franciscan houses at Apulia and Rome (26 October 1290). In 1290 Llull visited Genoa, where he completed an Arabic translation of the Ars inventiva, and then Rome, where he presented to Pope Nicholas IV his first treatise advocating a crusade, the Tractatus de modo convertendi infideles. Llull's proposals were not received favourably, despite the eventual fall of Acre in 1291 and a renewed crusading fervour in Europe; he returned to Genoa, whose citizens welcomed him and his plans.

In Genoa Llull suffered some kind of spiritual crisis: he vacillated with anguish between joining the Dominican or Franciscan orders; the former had already rejeceed his Art, but a revelation indicated that it was his only path of personal salvation; he eventually joined the Franciscans, whose vows hc took at the rank of tertiary. Deciding ultimately on an overseas mission, Llull enlisted the support of James II of Aragon, who recommended him to King Abu Hafs Omar I of Tunis, where Llull arrived in mid-1293. Adopting a common Dominican tactic, Llull challenged local Islamic scholars to a debate on the relative truth of their faiths, which led to his speedy banishment from Tunis and return to Naples. He visited Majorca briefly again in 1294. Llull continued to entreat the Papacy. After the renunciation of the Holy See in 1295 by the hermit Pope Celestine V, Llull directed his recently composed Disputació dels cinc savis and Petitio Raymundi (which urged missions to the Tartars) to Celestine's successor, Boniface VIII. At Rome between September of 1295 and April of 1296, Llull completed the greatest of his encyclopaedic works, the Arbre de sciencia. After visiting James Il of Majorca at Montpellier, Llull returned to Paris for three years, where he disputed with the 'Averroists' and sought the aid of Philip the Fair. Llull supported Philip's campaign against the powerful Templar Order as a means of achieving his own goal, the unification of all the military orders for a general crusade. At Rome once more in 1299, his views were heard with little enthusiasm, and he went from there to Barcelona. At the court of James II of Aragon, Llull received permission to proselytize the Moors within James's realm, and dedicated more works to him and his wife, Blanche of Anjou, before returning to Majorca.

After 1300 Llull's original literary production diminished considerably; he turned instead to the revision and amplification of earlier works in order to complete the envisaged universal scope of his Art. He also abandoned - temporarily - the advocacy of further crusades and undertook a missionary journey to the eastern Mediterranean. ln Cyprus King Henry de Lusignan II refused Llull's request to proselytize the Eastern monophysites; he held disputations with Orthodox theologians, but quickly departed after an attempt on his life. While at Limassol Llull met the last Master of the Temple, Jacques de Molay (burnt at the stake in 1314), who obtained permission for Llull to visit Armenia, a Templar ally. Llull travelled to Armenia, and perhaps to Jerusalem, during 1301 and 1302.

From 1302 to 1308 Llull lived alternately in Genoa and Montpellier, centres of support and patronage for him, and wrote a number of works. These included especially the Liber de ascensu et descensu intellectus (March 1304), the most refined statement of Llull's contemplative programme, and the Liber de fine (April 1305), the most complete expression of his missionary and crusading plans.

Llull failed in new attempts to interest Clement V, the first Avignon Pope, and the Genoans in a crusade. Only James II of Aragon responded to Llull's proposals with the ill-fated seige of Almería in 1309. In 1307 Llull embarked from Majorca to Bougie for his third overseas mission. There he was immediately imprisoned, but then exiled by its king at the request of James II of Aragon. On the return voyage, Llull was shipwrecked and rescued by vessels from Pisa, whose citizens supported him generously. At Pisa in 1308, Llull completed his Ars generalis ultima (begun in November of 1305), and its epitome, the Ars brevis.

Llull made another round of visits to the Pope at Avignon, the Pisans, and the Genoans in order to promote unsuccessfully the crusading proposals set out in his Liber de acquisitione Terrae Sanctae (March 1309), which supported the French campaign against the Byzantines. In 1309 Llull made his last visit to Paris, where, despite 'Averroist' opposition, he publicly read his Art and received the commendation of forty masters of the universiy (February 1310), Philip the Fair (August 1310), and the Chancellor (September 1311). This was Llull's last appeal for support to his powerful patron of nearly twenty-five years. In 1311 an account of Llull's life, known as the Vita coetana, was composed, perhaps from his own recollections, at the Carthusian house of Vauvert outside Paris; a large collection of Llull's works was kept there and it remained a major centre of Lullism after his death. That same year Llull wrote several short tracts in preparation for attending the Ecumenical Council of Vienne. Lo concili set forth his three goals; conquest of the Holy Land, writing books to prove the Faith, and establishing language schools. The Papacy fulfilled this last proposal with the creation of language chairs at major European universities in I312. En route to Vienne, Llull composed the Disputatio Raymundi phantastici et clerici and at the Council presented his Petitio Raymundi in concilio generali ad acquirendam Terram Sanctam.

The portrayal of himself as a phantasticus or as 'Ramon the fool' in the Blanquerna (82. 6) is an entirely probable representation of how his contemporaries regarded him. They never did consider his proposals worthy of their material support, and after 1311 Llull appears to have abandoned entirely the idea of a crusade. He returned to Majorca, where, nearly eighty years old, he dictated a will on 26 April 1313. In it he provided especially for the posthumous disposition and dissemination of his writings. Finally Llull went to Messina to appeal to Frederick III of Sicily, a friend of the Spirituals with an interest in overseas missions, but Llull received no support from him either. After completing various short works there, Llull undertook one last mission to Tunis, arriving there in November 1315. His last work, the Liber de maiori fine intellectus, amoris et honoris, is dated Tunis in December 1315. Llull died early the next year, martyred at Bougie according to one probably apocryphal tradition, or more likely upon returning to his native Majorca, where he was buried in the convent of Saint Francis.

Bibliography:

- Cruz Hernández, Miguel

- El pensamiento de Ramon Llull. - Valencia : Fundación Juan March, 1977. - (Pensamiento Literario Español ; 3)

- Hillgarth, J. N.

- Ramon Lull and Lullism in fourteenth-century France. - Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1971. - (Oxford-Warburg Studies)

- Johnston, Mark D.

- The spiritual logic of Ramon Llull. - Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1987.

- Sletsjøe, Leif

- Ramon Llull : humanisten fra middelalderens Mallorca. - Oslo, Cappelen, 1975. - (Uglebøkene ; 126)

- Yates, Frances A.

- Lull & Bruno. - London : Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982. - (Frances A. Yates. Collected essays ; 1)

Sist endret: 17 august 1994

Jan Frederik Solem / jan-fr@pclan.bibhs.no

Share: